History

From ‘stone house’ to ‘country house’

In 1536 there was still no castle in Hingene, but only the ‘stone house' belonging to Thibault Barradot. He was the high bailiff, receiver and steward to the count of Flanders, his representative in the manor of Bornem. The house was traditionally built in brick and sandstone with a rectangular ground plan. It consisted of a richly-decorated main hall and three other rooms and was surrounded by a moat. Around 1550 Thibault Barradot was forced to sell his house to raise money for repairs after extensive flooding had damaged the dykes. The new owners were the noble Antwerp family of van de Werve. The stone house was transformed into an aristocratic country residence,an L-shaped building with splendid reception rooms and an open gallery. There was a separate dovecote and the whole was surrounded by a moat. The estate also included a courtyard, stables, barn, vegetable gardens, orchards and fishponds as well as woods for timber extraction.

The country house

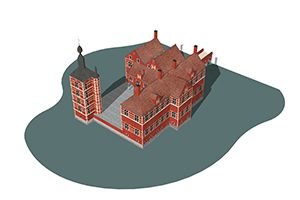

In 1608, the estate was bought by Conrard Schetz. Originally from Germany, Schetz’s grandfather and father had established themselves as merchants and bankers in Antwerp. They also held financial positions in the city and state administration. In this way the merchant family gradually became landowners and members of the nobility. Conrard Schetz expanded the Hingene manor house into a castle, with a second tower ,a further gallery and a monumental façade to the new main entrance. This was symbolically directed towards the village, as a sign of his noble and feudal power over the manor of Hingene. Finally, Schetz allowed himself to be adopted by his rich, unmarried aunt, Barbara van Ursel, and the Schetz family accordingly became the d'Ursel family.

A castle fit for a Duke

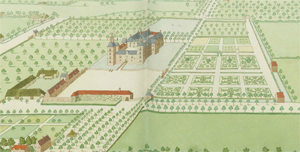

Generation after generation, the d'Ursel family climbed the ladder of nobility. By 1600 they were barons, by 1638 Counts and in 1717 Conrard-Albert became the first Duke. He was also doing well financially, thanks to an inheritance from a nephew who died childless. Hingene was his favourite residence and he had grand plans for it. Jean Beausire, architect to the King of France, was employed to transform the castle into a modern, fashionable residence in keeping with the Duke's status. The front of the building was given a late Baroque façade. Behind it an imposing reception room replaced the inner courtyard. To the left, the gallery made way for a residential wing with an apartment in the French manner. The garden, too, was redesigned in the French style, with a large reflecting pool and geometric parterres.

Classical monumentality

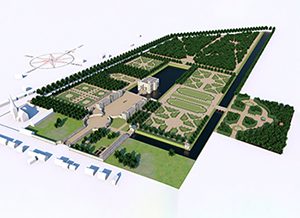

Half a century later, rigid classicism had become the fashion. Charles, the second Duke, in his turn hired a celebrity architect, one Giovanni Niccolò Servandoni, who had earned his spurs as a set designer in the theatre. His makeover of Hingene in 1761 was primarily intended to impress. The façade was raised in height by means of a curtain wall, behind which is empty space, and the towers were given classical balustrades instead of tented roofs. The old external traces of construction were concealed beneath a layer of stucco to create a harmonious classical whole. Servandoni reorganised the castle and the domain along a central axis: from the forecourt via the terrace and the reflecting pool to the patte d’oie in the woods of the park. Inside, the rooms were divided into a system of apartments. Originally Servandoni had wanted to make the entrance area and the court of honour more monumental still, but this proved not to be financially viable.

The metamorphosis of the estate

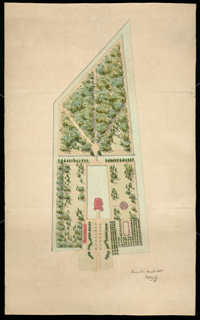

By the 19th century, the monumental renovations were over. The interiors were occasionally adapted to the latest fashions, but no fundamental changes were made. Joseph, the sixth Duke, did ask the famous German landscape architect Eduard Keilig to make plans for the estate.The basic structure of monumental sightlines was retained, but the classical layout made way for a landscape design with sloping lawns, picturesque groups of trees, wooded areas and a rose garden. A new garden pavilion in the Flemish Neo-Renaissance style was built in the woods and this would be used as a painting studio or atelier by Antonine, the sixth Duchess, a gifted amateur artist.

Sale and new life

In 1973, Henri, the eighth Duke, decided to sell the castle and park. The estate first went to the municipality of Hingene, then, after the1977 merging of Belgian local authorities, to the municipality of Bornem and finally to the Flemish Community. After it had lain empty for almost twenty years, the Province of Antwerp bought the estate in 1994 and lovingly restored it to its former glory. Now the restoration is complete, the Province is pursuing its mission to bring new life to castle and park, so that the history of the estate and those who lived there never cease to be an important source of inspiration.